In the tranquil waters east of Malaysia, far from prying eyes, an extraordinary operation is unfolding—a covert network of aging tankers, flagged under obscure nations, quietly moves hundreds of millions of barrels of oil. This “dark fleet,” as maritime experts call it, operates in a legal gray zone, evading sanctions, dodging regulations, and reshaping global oil trade dynamics. Beneath the surface lies a tale of economic survival, geopolitical tension, and environmental peril.

The Art of the Ship-to-Ship Transfer: A Covert Dance

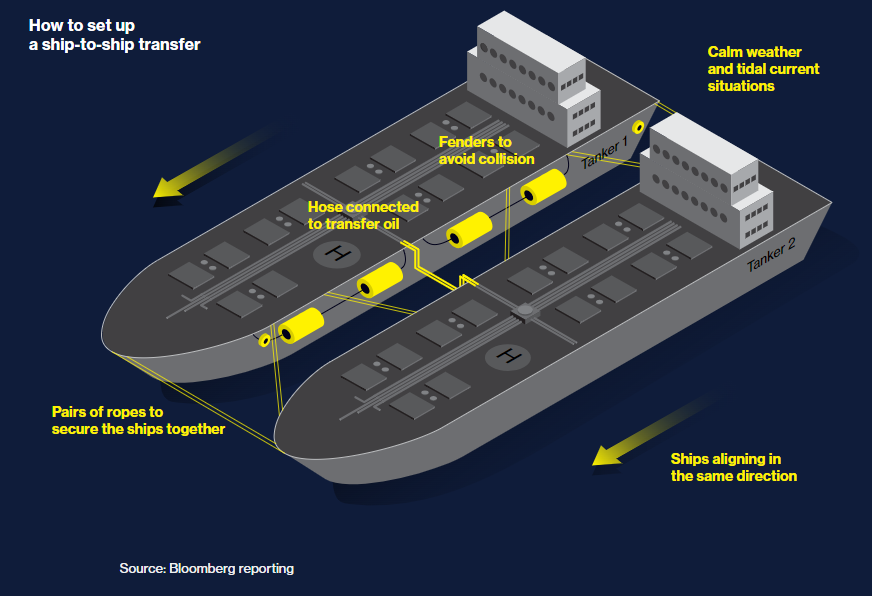

At the heart of this operation is the intricate and highly orchestrated process of ship-to-ship (STS) oil transfers. Far from ports and authorities, shadow fleet tankers engage in a delicate exchange, moving sanctioned crude oil from one vessel to another. Here’s how they do it:

- Positioning the Ships: Two tankers rendezvous in open waters, often in the cover of night. They align parallel to each other, carefully maintaining a safe but close distance. Calm weather and stable tidal conditions are critical to minimize the risks of collision or spillage during the operation.

- Securing the Vessels: The ships are tied together using pairs of mooring ropes, creating a secure connection while still allowing some flexibility. These ropes are continuously adjusted by the crew to ensure that the tankers don’t drift apart or crash into each other.

- Collision Prevention: Fenders—large inflatable or foam-filled bumpers—are strategically placed between the ships. These fenders act as a protective cushion, absorbing any impact and safeguarding the hulls from damage.

- Aligning the Vessels: The ships are carefully aligned in the same direction, facing into the wind or current. This alignment stabilizes the operation, ensuring the ships remain steady despite external forces.

- Connecting the Hoses: A hose system is set up between the tankers, connecting the oil tanks of both vessels. These hoses are designed to handle the high-pressure transfer of crude oil while minimizing the risk of leaks.

- Commencing the Transfer: Pumps onboard the source tanker (often the one carrying Iranian crude) begin the transfer process. Crude oil flows steadily through the hoses into the receiving tanker, while both crews carefully monitor the operation to prevent overfilling or spillage.

- Maintaining Balance: As oil is transferred, the weights of the tankers change dramatically. Crews adjust ballast tanks to maintain the ships’ stability and prevent them from capsizing.

This meticulous process, though not inherently illegal, raises significant concerns when used by the shadow fleet to evade international sanctions. Without proper oversight, these transfers carry significant risks, including oil spills that could devastate the region’s ecosystem.

A Ghost Fleet in Plain Sight

About 40 miles off the Malaysian coast lies a maritime anomaly: the world’s largest gathering of shadow tankers. These vessels, many decades old and uninsured, arrive daily to conduct ship-to-ship transfers of sanctioned Iranian crude, destined for China. Officially, China hasn’t imported Iranian oil in over two years. Yet, a sophisticated network of intermediaries, shell companies, and clandestine rendezvous ensures that billions of dollars’ worth of crude bypasses sanctions annually.

A five-year analysis of satellite imagery reveals the sheer scale of this shadow industry. Transfers in this hotspot have doubled since 2020, with some days seeing over a dozen such exchanges. Bloomberg estimates that in the first nine months of 2024 alone, at least 350 million barrels of oil changed hands in this area—a conservative estimate worth over $20 billion, even after steep discounts for sanctioned crude.

The South China Sea: A Perfect Stage for the Illicit Trade

This clandestine hub is strategically located. Nestled in Malaysia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), it is close enough to major shipping lanes yet beyond the direct enforcement reach of coastal nations. Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore appear unwilling—or unable—to intervene, leaving the region’s economic lifeline vulnerable to exploitation.

Dark fleet tankers often switch off their transponders, sailing “in the dark” to evade detection. Satellite images captured ships in telltale side-by-side formations, a clear sign of oil transfers. Most vessels are flagged to nations with minimal regulatory oversight, such as landlocked Eswatini or Mongolia. Many are well past their prime, operating without proper safety checks, insurance, or even clear ownership.

The Titans of Secrecy

Among these ships, the Titan, a 21-year-old vessel infamous for carrying Iranian oil, exemplifies the shadow fleet’s operations. Frequently spotted in side-by-side transfers, it is known to load crude from Iran’s Kharg Island before embarking on a zigzagging journey to Southeast Asia. Similarly, the Win Win, another aging tanker, shuttles between China’s Qingdao port and Malaysia’s waters, ferrying oil under the radar of international authorities.

These ships represent just a fraction of the estimated 800 vessels operating outside the norms of the maritime industry. With no legitimate insurance and dubious ownership records, they pose a looming environmental threat. A single spill from one of these tankers could devastate the ecosystems and economies of the region’s coastal nations, where fishing and tourism are vital industries.

Why This Matters: A Battle of Interests

For Iran, selling oil via these covert channels is a lifeline amid crippling U.S. sanctions. For China, this shadow network offers a cheap source of crude for its refineries while shielding major corporations from the risk of secondary sanctions. The U.S., despite imposing penalties, struggles to contain this vast and decentralized operation. Malaysia and its neighbors, bound by limited enforcement capacity and diplomatic neutrality, have little incentive to act.

Environmental and maritime experts warn that the risks extend beyond economic and political concerns. Without proper oversight, accidents involving uninsured dark fleet tankers are inevitable. Oil slicks are already spotted regularly in Malaysian waters, and with tankers carrying up to 300,000 tons of crude, a catastrophic spill is only a matter of time.

A Global Problem Without Easy Solutions

The scale and sophistication of the shadow fleet underscore the difficulties in enforcing international sanctions. Even with advanced satellite imagery and tracking algorithms, most illicit transfers occur unnoticed. Coastal states often lack the resources or jurisdiction to intervene, and global bodies like the International Maritime Organization have little authority over operations in international waters.

The Strait of Malacca, a crucial artery for global fuel transport, now faces increasing risks from these shadow operations. Calls for stricter monitoring and international cooperation grow louder, but unless backed by funding and enforcement capacity, these efforts remain symbolic.

A Warning Sign for the Future

The rise of the dark fleet is more than just a story of smuggling—it’s a reflection of the shifting dynamics of global trade and power. With traditional enforcement mechanisms struggling to keep pace, illicit networks like this will continue to thrive. Without coordinated action, this hidden armada will remain a volatile force in the world’s busiest waters, risking both environmental disaster and economic instability.

As the world watches the South China Sea, the question remains: how long can this secretive trade persist before its hidden costs erupt into plain sight?